I love my job as a Kuoda Travel Designer and blog writer because I can continually write about and share fascinating aspects of Peruvian cultural traditions. And making the pilgrimage to Qoyllur Rit’i is one of those utterly unique experiences that will forever tie you to Peru in the most surprising way.

In this article, we want to share this festival’s intriguing history, guided by my own experience when I made the journey in 2012. Here, you will learn what to expect on the climb to Qoyllur Rit’i if you decide to incorporate it into your own itinerary. We hope to inspire some of you to consider this experience for yourselves during your bespoke journey to Peru.

What is the Qoyllur Rit’i festival?

Something everyone should understand before arriving in Peru is that it is a Catholic country. Still, it is very much a syncretic one, meaning that Andean cosmology and spiritual tradition live alongside Catholic belief. To this day, many vital rituals, ceremonies, and, in the case of Qoyllur Rit’i, pilgrimages celebrate Catholic figures and apus (mountain deities) and Pachamama (Mother Earth).

Put very bluntly, the Señor of Qoyllur Rit’i (the Lord of Qoyllur Rit’i) symbolizes Jesus Christ, even though the Quechua phrase Qoyllur Rit’i literally means “the snow star.” The great festival of Qoyllur Rit’i reflects the Catholic Church’s attempt to erase Andean cosmology in favor of Catholicism. But what actually happened is they inadvertently led the way for a contemporary syncretic belief system.

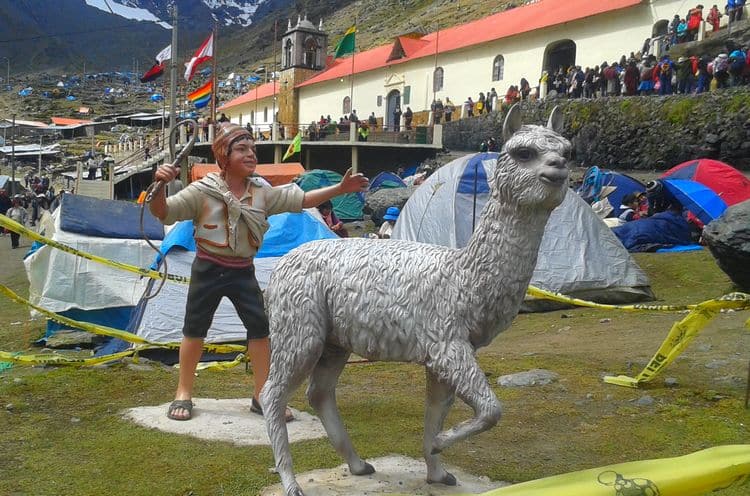

The origin story of this modern-day Peruvian pilgrimage goes something like this. In 1780, a supposed miracle occurred in the Cordillera Vilcanota of Peru, at the base of the range’s most impressive mountain glacier and apu: Ausangate. A young peasant boy named Mariano Mayta had been sent to tend his family’s llamas at this unlivable altitude.

Mariano nearly died when a young misti (a white boy) appeared to him wanting to play. They became fast friends, and the misti magically provided clothes, food, and comfort. Mariano wanted to thank his new friend, and so he went to the archbishop, who in turn desired verification of the misti’s existence.

When they finally arrived, the archbishop was astonished by the misti’s radiance. He leaned in to touch the boy’s arm and was left holding a crucifix. Mariano, shocked at what had happened to his new friend, died on the spot and was buried under a nearby rock.

It is important to note that this was around the same time as the last stand of Tupac Amaru II and his rebellion against the Spaniards, against Catholicism. It is also of note that this place on Ausangate previously held great spiritual significance for Quechua communities who worshiped the apus and Pachamama.

When and where is Qoyllur Rit’i celebrated?

The festival takes place in late May or early June, depending on the Andean calendar. I made the pilgrimage to the Ausangate glacial valley at almost 16,500 feet above sea level to pay homage to El Señor de Qoyllur Rit’i in early June 2012.

Every year, thousands of people trek for about 3-5 hours from the starting point at a town called Mahuayani to the sanctuary built in this misti’s honor (allegorically speaking in Jesus Christ’s honor) within the Ausangate glacial valley. There is a cross every two kilometers along the trail for the masses to stop, pray, dance, and sing.

Once at the sanctuary, the song and dance continue to radiate through the usually silent landscape for three days. More than thirty naciones (the name granted to each community) represent the vastly diverse Peruvian indigenous cultures including Quechua and Aymara-speaking communities. Believers do not underestimate the importance of trekking to Qoyllur Rit’i three consecutive times; because if one fails to do so, bad luck will fall upon their family.

How to arrive at the Qoyllur Rit’i snow star festival?

Bear in mind, my experience arriving at Qoyllur Rit’i was before I started working for Kuoda. So, if you book this festival through us, we will provide private transportation to Mahuayani and private tents with your private guide at every point of the journey. Nonetheless, this was my experience traveling like a local in 2012; and you will be sure to connect with many locals through your guide once you arrive.

We arrived at Mahuayani about four hours late on June 2nd, after waiting in Cusco, somewhat patiently, for the bus to fill every last seat. An overwhelming number of buses queued for a shocking number of people. Panchito, my music instructor and connection to the Hatun Q’eros Quechua community, flashed me a knowing grin of “this is how it is,” and began to yell the same call of desperate bus drivers, “MAHUAYANI, MAHUAYANI, MAHUAYANI QUINCE SOLES.”

I bought a bag of canchita (toasted Andean corn) while we waited. Then when the bus began to rapidly climb hundreds of meters, I traded the salty kernels for my ch’uspa (woven satchel bag) stocked with sacred coca leaves to fight the inevitable head pressure of soroche (altitude sickness).

By the time we arrived at the gateway town of the Ausangate glacial valley, the darkness had already disguised a stark highland landscape. We then weaved between tents upon tents of temporary vendors providing scalding caldo de gallina (hearty chicken soup) and tepid chicha morada (purple corn soft drink) prepared just a few hours before.

We finally made our way to the Hatun Q’eros camp, visible only by starlight. A double-voiced quena flute melody pierced the distance between our group of five urban dwellers and the Quechua community that had graciously invited us to join them.

The male elders of the community and two quena players recognized Panchito at once as he approached them, matching their melody with his own quena flute. I felt distinctly goofy in my extra-large snow pants, puff jacket, wool hat, and mittens; however, I was greeted just the same as the others.

The quenas and dancing feet did not rest that night. I watched Panchito and the other men in my group warm themselves through movement while anise liqueur and cane alcohol coursed through their bodies. Right then, a hand pulled me up into the dancing ukukus (the mythological man-bear and guardian of the festival). The hand was that of a Cusqueñan woman. Together, we watched the ukukus swirl around us, play and jest as a part of their adopted mythological persona.

The next day, just as the sun kissed the base of the mountain, we started our trek, stopping briefly every two kilometers at the designated crosses. Five hours and just over five miles later, we met thousands of others at the base of Ausangate.

Dancers, musicians, ukukus, children, and tourists alike had amassed in the glacial valley. They created transitory housing beneath tents and tarps. I felt the palpable energy emanating from the surrounding bodies and the apu spirit itself as we searched for an available square of space to lay our tarp.

What is the festival celebration like?

After settling in at the designated campsite, I began to note the many dances and rituals associated with El Señor de Qoyllur Rit’i, which are performed on-site within each nación. One of the most dominant of these rituals is called Yawarmayu, which in Quechua means “river of blood.”

Yawarmayu is the dance of the ukukus. You will recognize the ukukus by their shaggy “fur” made of multi-colored yarn and full head mask, mimicking a bear. They also carry a small plastic bottle around their necks to create a high and clear whistle sound, and most importantly, they don a whip.

For Yawarmayu, the whip is an essential prop, and the dance always proceeds in the same fashion. First, a pair of ukukus link arms and dance together forward and backward. Then a different melody marks the exchange of mock lashings, after which they continue to dance in a circle around each other.

When the tempo and excitement of the melody increases, they continuously lash one other and sometimes, although very rarely, draw actual blood. All the while, they laugh. Finally, a different ukuku breaks up the “fight” by jumping enthusiastically in the middle of the first two. It is pretty exciting and symbolizes honor, trust, and brotherhood.

I noticed the iglesia (the church) almost instantly. I decided not to enter because of the extremely long line and because I am not Catholic. However, it was enough to witness the deep devotion and faith of the crowds during mass. Everyone peeled off their chullos (ear-flap hats) and prayed as the bell chimed.

Meanwhile, at our camp, I noticed the Hatun Q’eros couldn’t care less about mass. Instead, every so often, a community member would pass around a bit of coca, anis liqueur, sugar cane alcohol, and cigarettes to honor Pachamama (Mother Earth). They did not enter the church, yet they represented an equally crucial spiritual faction in the festival at large.

After sunset that night, I partook in a bit of anis liqueur myself. I then snuggled as deep within my sleeping bag as I could manage before pulling another plastic tarp over my entire face and body. To this day, I have never slept so soundly or peacefully, despite the continual ruckus surrounding me. I wonder if Pachamama’s presence, the apu Ausangate, or Jesus Christ himself had anything to do with that.

If we have piqued your curiosity about Peruvian religion and culture and you are considering an exclusive tour to Peru in May or June 2022, we encourage you to make the journey through Mahuayani up into one of the few remaining Andean glaciers. The ukukus await you! To learn more about this Andean pilgrimage, we would be happy to help out in any way we can. Contact us!